The CM Knew Your Caste. Your Sister's Name. The CM Never Made the Call.

What happens when the Chief Minister calls to thank you personally, but never made the call? Agentic AI is transforming Indian elections from content creation to autonomous persuasion. The 2026 state polls are the laboratory. UP 2027 is the test. 2029 is the prize.

ELECTIONSPOLITICSINDIAARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCELEADERSHIPPOLITICAL STRATEGYCOMMUNICATION

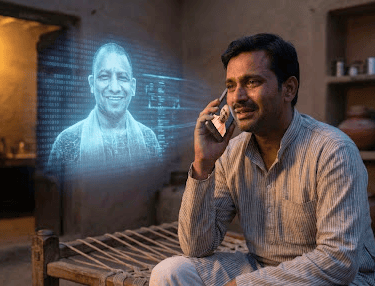

In February 2027, Vikas Dhimar, a booth agent in Moharipur, Gorakhpur, gets a call from a Lucknow number. When Truecaller displays "CM House," he feels excited. The Chief Minister's operator says the CM wants to speak and connects the call.

"Vikas, is that you?" the CM asks, sounding warm and familiar. He thanks Vikas for his work registering voters in Shivpur, then asks, "How is your sister's college admission going?" After speaking with him for around two minutes on various topics, he brings up the Nishad community's concerns about river dredging permits and promises to get things in order as soon as possible.

Later, Vikas shares his experience on WhatsApp and social media. He is surprised that the CM, despite leading the state, remembered his name, his sister, and local issues. These details make Vikas feel noticed and valued.

However, the CM has no idea about this call. He is actually at a rally in Deoria. A server in Noida starts the call, using a synthetic voice clone trained on two years of the CM's speeches. An AI system manages the conversation in real time, using Vikas's activity logs, family details from social media, caste from surname analysis, and his area's grievance data from the IGRS portal.

This scenario is fictional. The technology is not.

In Bihar's November 2025 elections, AI chatbots sent personalised messages to voters in local dialects, even during the 48-hour silence period when regular campaigning was banned. Voice clones of candidates called voters, who did not realise they were speaking to a machine.

The real question is not if AI will change Indian elections, but who will master it first and what that means for the 543 Lok Sabha seats in 2029.

From Generative to Agentic: The Real Shift

In my previous article, I discussed generative AI: deepfakes, voice clones, and translation tools. These remain important. But the 2026 elections will bring a bigger change, a shift from generative to agentic AI.

Generative AI makes content when you ask for it. You give a prompt, and it responds. Agentic AI, on the other hand, can carry out tasks on its own. You set a goal, it plans the steps, takes action, and adjusts based on what happens.

Gartner predicts that by 2028, AI agents will make 15 per cent of daily work decisions, up from almost none in 2024. The AI agent market is growing by 46 per cent each year.

Think about how voter outreach works today. Campaigns use data analytics to find target voters and assign them to volunteer teams. Volunteers send messages, make calls, and record responses. Managers review reports, adjust targeting, and move resources as needed. This process takes hundreds of people working over several days.

An agentic AI system can do all this in minutes. It can find targets, create personalised messages, send them on different platforms, analyse responses, and adjust the strategy right away. It can work across every constituency at once and keep thousands of conversations going without fatigue.

If a controversy comes up, the system can quickly spot the affected constituencies, create tailored responses, send them through the right channels, and measure the reaction. All this can happen before a human campaign manager finishes their morning tea.

A traditional campaign would have to hire enough staff to contact every persuadable voter in UP, costing hundreds of crores in salaries. An agentic system can reach just as many people for much less by investing in infrastructure instead of labour. Human campaign teams break up after each election, but agentic systems keep all their knowledge. The machine holds the institutional memory.

In November 2025, Anthropic reported what could be the first cyberattack mainly led by autonomous agentic AI. If bad actors can use AI agents for hacking, political groups can use them for persuasion. The technology is the same.

80 Seats, One Test Run

Uttar Pradesh sends 80 members to the Lok Sabha, about 15 per cent of the total. Since 1984, every central government has needed to do well in UP. The state's 403 assembly seats, up for election in February-March 2027, are more than just about Lucknow. They are a test run for Delhi.

The party that masters AI-driven campaigning by 2027 will enter 2029 with strong infrastructure, efficient workflows, and valuable experience. The party that falls behind may never catch up.

Here's the timeline that matters. As I write this in the last week of December 2025, campaign machinery is being assembled. The BJP has named Pankaj Chaudhary, a Kurmi, as UP state president in direct response to losing non-Yadav OBC votes. The Samajwadi Party is organising "PDA Chaupals" to bring together backward classes, Dalits, and minorities.

Between March and May 2026, Bengal, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, and Assam will vote, deciding about 824 assembly seats. AI tools will be tested on a large scale. From June to December 2026, parties will review the results and refine their strategies. The plan for UP will become clearer.

In early 2027, the UP campaign starts. Panchayat poll results will show which booth-level strategies worked. Between February and March 2027, UP will vote to elect 403 members. This is the real test. Elections in Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, and Telangana in 2027 and 2028 will allow for more adjustments. Then, in 2029, the Lok Sabha elections will see all strategies in action and the stakes at their highest.

The 2026 Laboratories

West Bengal

West Bengal is the BJP's biggest expansion target outside its usual strongholds. Amit Shah will spend more time in West Bengal in early 2026 than in any other state, even Delhi. The BJP's Mission 2026 aims to win 200 of 294 seats. This is not just ambition; it is a major commitment backed by the party's extensive resources.

The BJP's recent panchayat results in Assam give a preview. The NDA alliance won 76 per cent of anchalik panchayat seats, defeating the "Three Gogoi Alliance" that aimed to unite opposition votes. The BJP thinks West Bengal can follow a similar path if it can solve the "Bengali identity" issue that has challenged its campaigns.

This is where artificial intelligence can make a real difference.

The BJP has already used Bhashini to translate Modi's speeches into Bengali, Tamil, Malayalam, and eight other languages. Industry estimates say over 50 million AI-generated voice clone calls were made in the two months before the 2024 general election. These were early versions. The tools for 2026 will be much more advanced.

The next generation of AI can check if a voter's social media posts use "Bangla" or "Bengali," mention "Kolkata" or "Calcutta," and whether their cultural references are to Rabindra Sangeet, Bollywood, or Tollywood. These small details show identity positions that human canvassers might miss.

When the opposition attacks, AI systems can quickly create targeted responses, translate them into local dialects, use synthetic candidate voices, and send them through WhatsApp networks that are hard to monitor.

Recent research from Cornell University is notable. In real election experiments in the United States, Canada, and Poland, AI chatbots shifted voter preferences by two to three percentage points. This effect lasted for a month and was stronger than traditional political ads. In West Bengal's close races, that margin could decide the winner.

The Trinamool Congress is ready. Abhishek Banerjee has started "Ami Banglar Digital Joddha" (I Am Bengal's Digital Warrior), a program to mobilise tech-savvy volunteers. The program has three types of digital workers: content creators, social media managers, and amplifiers. It is a human answer to a machine challenge.

Still, the gap remains. The BJP has far more resources than regional parties. One data centre in Navi Mumbai can handle more voter interactions in an hour than a thousand volunteers can in a month. More money buys not just ads, but also infrastructure.

Bengal will show if AI-driven outreach can beat strong regional parties, if targeting language and culture can reduce identity politics, and if bigger resources lead to election wins.

Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu is different. Here, AI meets a significant political change: the entry of Thalapathy Vijay and his Tamilaga Vettri Kazhagam (TVK).

Vijay's party plans to contest all 234 seats on its own. It calls the BJP its "ideological enemy" and the DMK its "political enemy." The party says it has over 70,000 trained booth-level agents. It also has something the DMK and AIADMK lack: a fan base already active on digital platforms.

Vijay's fan clubs reportedly number about 85,000 across Tamil Nadu, each with at least 25 members. These supporters are active, organised, and comfortable with digital tools. They already use WhatsApp to coordinate, share content on Instagram, and mobilise for events.

A recent OneIndia poll showed a clear pattern. TVK leads on Instagram. The DMK dominates on Facebook and also leads on X (formerly Twitter). The platform demographics tell the story: younger voters, who use Instagram more, prefer Vijay. Older voters, who use Facebook, prefer Stalin.

What if TVK uses AI tools with its existing fan network? The party does not need to build a digital army—it already has one. It just needs better tools.

The DMK is responding with its own membership drive, "One Voice for Tamil Nadu," aiming to enrol 30 per cent of voters in each constituency. However, Chief Minister Stalin's strength is governance, not technology. The DMK's welfare schemes, free bus travel for women, and educational reforms are hard to explain through algorithms. They need time, trust, and direct experience.

The main question is whether TVK's entry will help or hurt the BJP's goals. If Vijay splits the anti-DMK vote, Stalin wins easily. If Vijay energises young voters while the BJP unites communal voters, the DMK faces a two-front challenge it has not faced before.

Tamil Nadu will show that AI will not decide the outcome, but will amplify whatever trends are already there. The technology itself is neutral. How people use it is not.

Assam and Kerala

Assam, where the BJP holds power and the opposition remains fragmented, will test the effectiveness of micro-targeting for minorities. The "Three Gogoi Alliance" (Gaurav Gogoi, Akhil Gogoi, Lurinjyoti Gogoi) collapsed in local body polls. Congress has ruled out an AIUDF alliance, risking a split in minority votes in 25 Muslim-dominated constituencies.

Kerala, the most literate state in India, will test if well-informed voters can spot manipulation. The LDF is aiming for a third straight term. The UDF is rebuilding. The BJP still struggles to gain ground.

If AI-driven disinformation fails anywhere, it will probably fail here first.

Uttar Pradesh: Where It All Converges

Uttar Pradesh is where India's political future will be decided, and where AI-driven campaigning will face its toughest test.

Unlike Bengal, where the BJP is the challenger, UP is the BJP's stronghold, now under threat. Unlike Tamil Nadu, where caste is organised around two main groups, UP's caste mix is much more complex: Yadavs, Jats, Kurmis, Lodhs, Rajbhars, Nishads, Mauryas, Koeris, Kewats, and many more. Unlike Kerala, where high literacy helps guard against manipulation, UP's rural areas have lower media literacy.

This is why UP is the real test. Not just another state election.

The BJP's Position

The BJP won UP in 2017, winning 325 of 403 seats. In 2022, they won 255, a majority, but 70 fewer. In the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, they won 33 out of 80 seats, down from 62 in 2019. The trend is clear: their hold is weakening.

The erosion is not uniform. Upper-caste voters, Brahmins, Thakurs, and Vaishyas, remain steadfast. The problem lies with non-Yadav OBCs: Kurmis, Kushwahas, Lodhs, Nishads, Rajbhars, and the Extremely Backward Classes.

The BJP's response is clear in recent appointments. Pankaj Chaudhary, the new UP BJP president, is a Kurmi. The party is using its "Bihar model" by giving more tickets to OBC and EBC candidates. Yogi Adityanath has told booth workers to check voter lists, warning that a gap of nearly four crore voters must be closed.

The SP's PDA approach (Pichhda, Dalit, Alpsankhyak) has built a social coalition that frames caste identity as part of a broader narrative of marginalisation. The BJP's response is more practical than narrative: reaching each group individually, at scale, with tailored messages. AI makes this possible.

The likely BJP workflow in UP 2027 starts with data enrichment, adding caste identification from surname analysis and local knowledge, consumption patterns from digital footprints, and social media sentiment to the voter database. AI then sorts voters into groups: soft Hindu, undecided Kurmi, SP-leaning Nishad, committed BJP supporter, unreachable Muslim.

Each group gets different messages through language models trained on BJP leaders' speeches. A Kurmi farmer in Pratapgarh gets agricultural content. A Nishad fisherman in Ballia hears about river-economy policies. A Rajbhar youth in Ghazipur receives information about reservations.

Messages are sent through voice clone calls, WhatsApp forwards, YouTube shorts, and Instagram Reels. Engagement data is fed back into the system continuously. Messages that work are shared more. Messages that don't are changed.

This is not just a theory. Bihar 2025 showed every part of this process in action. UP 2027 will use it on a scale five times bigger.

The Samajwadi Party's Challenge

The SP's advantage lies in its organisational depth. Akhilesh Yadav's booth-level network, rebuilt after the 2017 debacle, performed remarkably in 2024. The SP won 37 Lok Sabha seats, its largest-ever haul.

But the SP lacks comparable resources. It cannot spend as much as the BJP, lacks access to government data, and has digital skills that need improvement. It attempts to create a new social coalition, not Yadav-plus-Muslim, but a broader "victimised" identity that includes non-Yadav backwards, Dalits, and minorities.

Akhilesh has promised to conduct a caste census within three months if the SP forms the government. This keeps caste awareness high without targeting each caste separately. SP workers report ground sentiment using structured apps. They spot issues before they become crises and focus on checking welfare delivery: Did you get your ration? Did the PM Kisan money arrive?

What the SP could do, but may not be doing: use AI sentiment analysis on its own reports, use AI to find patterns across 403 constituencies, train language models on Akhilesh's speeches for personalised outreach, and create AI-driven rapid responses to counter-narratives.

If the SP loses UP 2027, one question will remain: could they have competed on technology, or did they give up that ground before the fight began?

Why This Article Focuses on the BJP

If you feel that this article has focused a lot on the BJP, it is because of its resources, not because of my personal bias. The BJP's financial strength is greater than that of regional parties and any other political party in India today. Its access to government data, Aadhaar, telecom records, and welfare lists gives it advantages that opposition parties find hard to match.

But the opposition is not standing still. Congress's digital operation has looked stronger in recent months. The Bharat Jodo Yatra created a lot of digital content. The party's 2024 campaign was more digitally advanced than any before.

Regional parties are building their own infrastructure. The DMK's membership drive includes a digital part. The TMC's "Digital Joddha" program trains volunteers. The Misinformation Combat Alliance started a Deepfakes Analysis Unit before 2024. They will be better prepared for 2026 and 2027.

The arms race is not one-sided. But the BJP starts with advantages that are hard to ignore.

The Regulatory Gap

India has no specific laws for AI in elections. The Election Commission issued an advisory in May 2024 warning against deepfakes. Parties must remove deepfake content within three hours of notice. But what counts as "notice" is unclear. The difference between a "deepfake" and legitimate AI-assisted content is also not defined. Enforcement is weak.

The IT Ministry has said it is not planning to make laws on AI. The advisory directives do not have legal force.

The EU's AI Act is different. Chatbots, deepfakes, and AI models used for political ads are considered "high risk" and subject to strict rules. India has nothing similar.

This gap helps those willing to push boundaries. A party that waits for ethical guidelines may end up following rules that no one else observes.

What Voters Must Understand

The "liar's dividend" is here. When real footage embarrasses a politician, they can say it is a deepfake. When opponents show evidence of wrongdoing, supporters dismiss it as AI-generated. Truth becomes about loyalty, not facts.

In 2024, the BJP accused Congress of making a deepfake of Amit Shah making controversial statements about reservations. The video was edited, not synthetic. But the accusation created confusion.

Citizens should know that personalised political messages may not come from humans. If a candidate sends you a WhatsApp message that seems to understand your concerns, ask yourself how they knew about them. The personal touch may be artificial.

Be sceptical of viral political content near elections. Explosive news rarely happens by accident. Look for primary sources. If a politician is said to have made an outrageous statement, find the original from a trusted outlet. Check if several independent sources have verified it. Remember, video and audio can be faked.

Most importantly, vote based on substance. Welfare schemes either work or they don't. Roads are either built or not. The things that affect your daily life are harder to fake than things that play on your emotions. Judge governments by their actions, not their stories.

What Political Practitioners Must Decide

I have worked in political communication for over ten years. The question my colleagues and I face is simple: where do we draw the line?

The technology itself is neutral. AI can translate speeches into regional languages, helping more people take part. It can analyse voter concerns, assisting parties to understand what people need. It can make campaigns more efficient.

But the same technology can also deceive, manipulate, and undermine. The difference is in how it is used and why.

I have been asked to create content that crossed ethical lines, and I refused. I know others who have accepted such requests. The market does not police itself. The only absolute limit is personal conscience.

Chanakya's advice is still relevant: before you start any work, ask yourself three questions. Why am I doing it? What might the results be? Will I be successful?

A strategist who uses AI to spread misinformation may win in the short term. But what have they created? A system where truth is unclear, voters trust nothing, and democracy becomes just a show.

Success should be measured over time. A party that wins by manipulation creates problems for society that come back as instability, cynicism, and a weaker democracy.

Five Futures

Scenario 1: The BJP's infrastructure makes the difference. Bengal is won, Tamil Nadu splits, and UP gives the BJP a third straight government. The 2029 model is set: whoever masters AI wins. Opposition parties try to catch up, but the gap is too big.

Scenario 2: TMC keeps Bengal through strong booth-level organisation and identity. SP holds UP by uniting PDA groups and highlighting welfare delivery failures through human networks. AI is less important than expected. Traditional political work still matters.

Scenario 3: Many deepfake controversies make people distrust all video evidence. Politicians use this to deny real scandals. Voter apathy grows, turnout drops, and whoever mobilises their base wins. Persuasion no longer matters.

Scenario 4: The ECI, learning from 2026, requires all AI-generated content to be disclosed before UP votes. It sets up a rapid-response verification team. Parties that break the rules face disqualification. AI use goes underground, and mainstream adoption is limited.

Scenario 5: Parties use agentic AI to truly listen, gather feedback, spot local issues, and adjust their manifestos to real needs. AI-to-voter dialogue goes both ways. Smaller parties reach more people than they could before.

And if our institutions' security and oversight fail, we could face a much darker scenario: voting manipulation using advanced AI tools.

We do not know which scenario will happen. We only know that the choices made in 2026 and 2027 will decide which one becomes real.

Where We Are Headed

The machines are learning to campaign. By 2027, they will have learned a lot. By 2029, they will know everything that worked.

Uttar Pradesh is the testing ground. It's not just about its size, though 80 Lok Sabha seats are important. It's not just about its complexity, though its caste mix challenges every strategy. It's because UP is where the BJP must defend its stronghold, and the opposition must show it can break through.

What happens in Bengal and Tamil Nadu in 2026 will set the stage. What happens in UP in 2027 will decide the direction. What happens in 2029 will shape Indian democracy for years to come.

The infrastructure is being built now. The models are being trained now. The strategies are being planned now.

Citizens who understand this have time to get ready. Political practitioners who understand this have time to make choices.

The question is not whether AI will change Indian elections. The real question is who will control that change, and for what purpose.

The machines are becoming intelligent. Are we?